The recent release of Richard Hessink's catalog raisonné of Banksy’s street works marks a monumental moment in the history of contemporary art. This catalog, spanning over 2,000 pages across three volumes, meticulously documents more than 10,000 individual street works by the elusive artist, who has become a cultural phenomenon. While only around 300 of these works have survived to this day, Hessink’s comprehensive work stands as a pivotal resource, both for the preservation of Banksy’s legacy and for understanding the artist’s place within the global art movement.

A catalog raisonné is a crucial scholarly document that provides a complete, systematic listing of an artist’s works. For artists like Banksy, whose creations often exist in ephemeral public spaces, the catalog becomes even more essential. Banksy’s street works, typically painted on walls, alleyways, and building exteriors, are subject to the ravages of time, weather, and human intervention. Some are erased, painted over, or simply fall victim to the ongoing changes in the urban landscape. Hessink’s catalog provides a unique and irreplaceable record of these works, ensuring that the artist’s full creative output can be studied, appreciated, and understood, even if the physical works no longer exist.

What sets this catalog apart is the sheer scope and depth of its documentation. Listing over 10,000 street works across 2,000 pages in a comprehensive three-volume set, the catalog offers an unprecedented survey of Banksy’s artistic evolution and output. These street works span over two decades, showcasing the artist’s relentless engagement with public spaces and his increasingly sophisticated political and social commentary. The catalog is not just a registry; it’s a vital historical and cultural document, encapsulating a time when street art began to transcend its origins as illicit graffiti to become a legitimate form of global artistic expression.

Banksy’s street works are inherently fragile. The artist’s decision to create in public, transient spaces was both a rebellion against the art establishment and a deliberate choice to engage directly with communities and audiences in urban environments. However, this ephemerality—coupled with the inevitability of urban development and gentrification—means that only a small fraction of these works has survived intact. The catalog’s inclusion of over 10,000 works highlights the vast body of work that has existed, but with fewer than 300 surviving examples, the catalog provides an essential visual and archival record that ensures Banksy’s Street Art is preserved, even as the physical pieces are lost to time.

For collectors, curators, and scholars, Hessink’s catalog becomes a critical tool in identifying and verifying authentic works, particularly as Banksy’s pieces have entered the realm of high-end auctions and prestigious galleries. The catalog serves as an authoritative reference, offering provenance and detailed descriptions for each work, making it an indispensable resource for anyone seeking to understand or engage with Banksy’s legacy.

Banksy’s work stands at the intersection of art, activism, and social commentary. By subverting traditional art forms and locations, Banksy not only challenges the art world but also questions societal norms. His street works often contain biting critiques of war, capitalism, environmental destruction, and social injustice. These works, though created in public spaces, resonate universally, breaking down the barriers between art and audience, gallery and street. Banksy’s ability to merge political message with artistic expression in a way that is both accessible and aesthetically powerful has made his street works an essential part of contemporary cultural discourse.

The catalog raisonné’s comprehensive documentation of these works allows for a deeper understanding of the socio-political context in which they were created. It’s a lens through which scholars, art historians, and the public can trace Banksy’s evolving political stance, his commentary on the commercialization of art, and his relationship with the public spaces he inhabits. For future generations, this catalog will serve as a record of an artist who was not only prolific but deeply engaged in the urgent issues of his time.

Banksy’s impact on the street art movement cannot be overstated. Though street art has existed in various forms for decades, it was Banksy who brought it into the global spotlight, blurring the lines between vandalism, art, and activism. By turning the streets into his canvas, Banksy redefined the boundaries of art and public space. His works transcended the traditional gallery system, engaging with a wider audience and democratizing art.

Hessink’s catalog offers a crucial snapshot of Banksy’s influence on the evolution of street art, highlighting how the artist's works have shaped the movement, inspired countless others, and raised important questions about the commercialization of art. As the first fully comprehensive account of Banksy’s street works, the catalog underscores the scope of the artist’s contribution to both the street art movement and contemporary art more broadly.

As the catalog raisonné stands as a critical and exhaustive record of Banksy’s street works, it also plays a key role in the preservation of his artistic legacy. While the fate of many of Banksy’s works is uncertain, the catalog ensures that they will not be forgotten. It guarantees that the message embedded in these works, which has resonated with millions of people worldwide, will continue to be studied, admired, and debated.

Furthermore, as the art market continues to commercialize street art, Hessink’s catalog can serve as a guiding resource in preserving the integrity of Banksy’s artistic vision. It can provide a counterbalance to the increasing commodification of street art, ensuring that the political and anti-establishment ethos of Banksy’s work remains intact even as it becomes part of the global art economy.

Richard Hessink’s newly published catalog raisonné of Banksy’s street works represents a defining moment in the preservation and scholarship of contemporary art. By documenting over 10,000 street works, Hessink provides an invaluable resource that will help preserve Banksy’s legacy for generations to come. As a document that captures both the breadth of Banksy’s artistic output and the socio-political messages embedded in his work, the catalog reinforces the significance of street art in today’s cultural landscape. It stands as a testament to the resilience of an art form that refuses to be confined to galleries and auctions, and to the lasting impact of an artist whose work continues to speak to the issues of our time.

Text ny Peter Hvidberg, 2025.

Order your copy here: https://richardhessink.com/

(Opens in another window).

Foreword by Richard Hessink, Author of the Raisonné.

Harvey Haddock – Provenance Evidence

Provenance is essential when it comes to the early Banksy street and street-related works.

And here is an example of how we build evidence to demonstrate that collaboration with Banksy is proven.

A frequently mentioned individual is a certain Harvey Haddock. I first came across the name as early as 2007, when I found a post on The Urban Art Association—also known as The Forum.

There, Harvey is referred to as Banksy’s dogsbody—meaning his helper and general assistant.

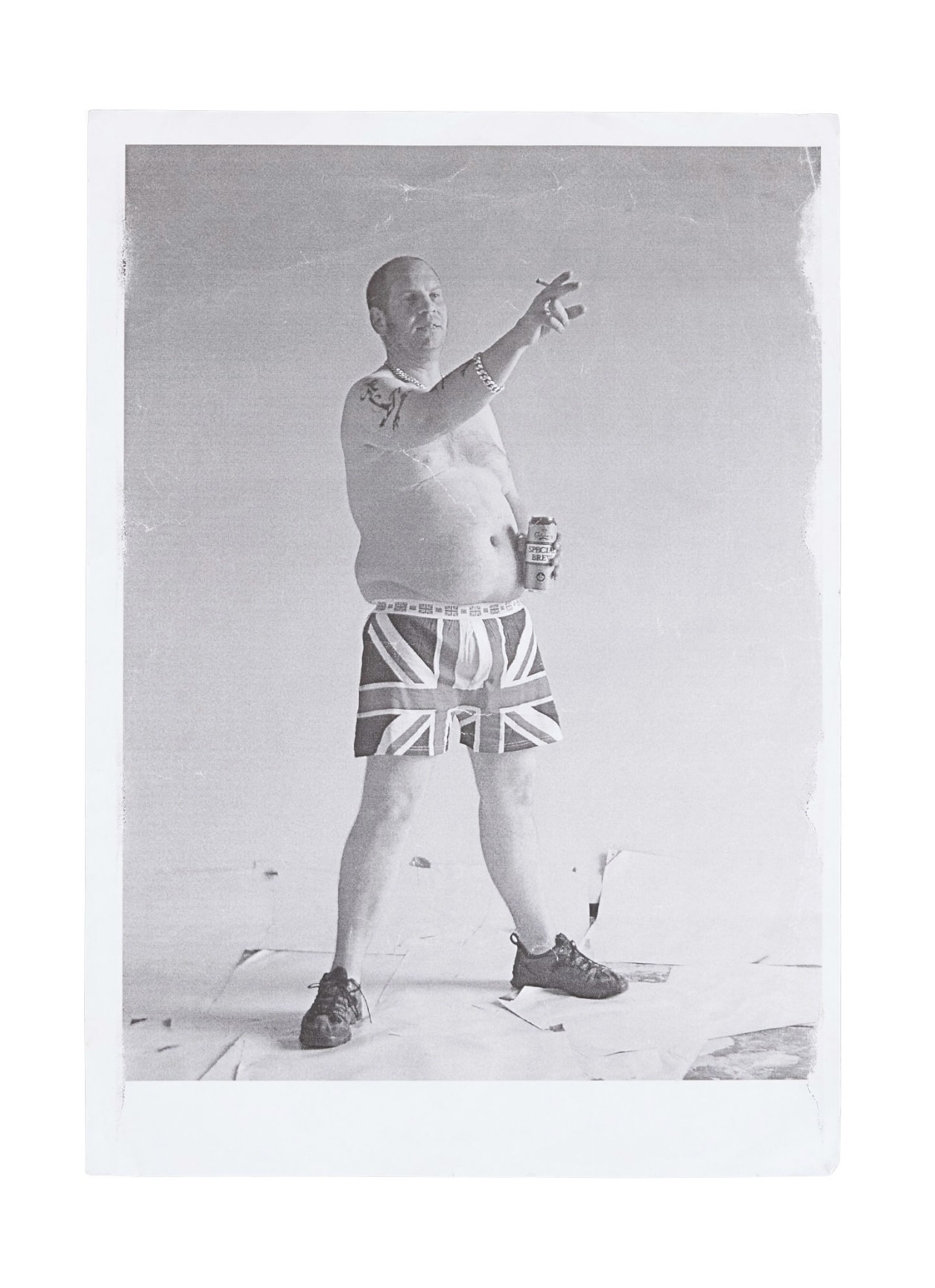

Rumors circulated that Harvey posed for Banksy when he painted his parody of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. In the painting, Harvey appears wearing only Union Jack boxer shorts, holding a can of beer (Carlsberg), just after having thrown a chair at the window—like a true hooligan.

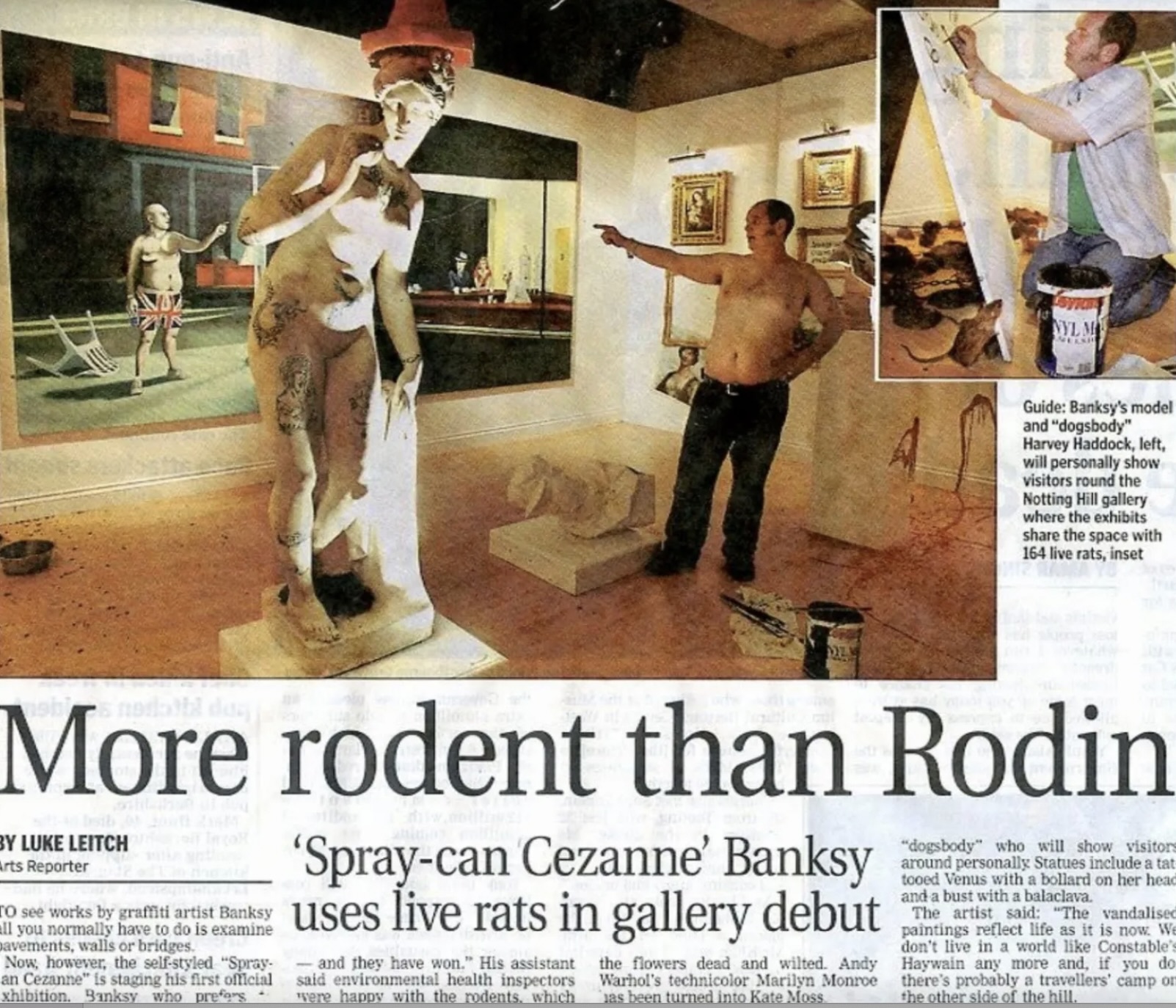

There also exists a contemporary newspaper article (2006) in which Harvey Haddock is photographed standing shirtless in the middle of the Crude Oils exhibition, pointing at himself in the painted version of Nighthawks. Once again, Harvey is referred to as Banksy’s dogsbody. The headline of the article was “More Rodent than Rodin,” naturally referring to the 150 live rats that had been released onto the exhibition floor.

So, to claim that there is little documentation proving that Harvey worked with Banksy can now be firmly dismissed.

Fast-forward to 2024, when Julien’s Auctions in Los Angeles held a special auction featuring items from the archives of Steve Lazarides. Here it becomes even more interesting.

Lot #48 is described as “Banksy hand-drawn name logo concept sketch.” But if you browse through the uploaded photos, you can see that the reverse side is a large photocopy of what the auction and Lazarides describe as “an unknown man.”

But he isn’t that unknown. It is, in fact, a photograph taken by Banksy of his assistant and friend Harvey Haddock, standing in Union Jack boxer shorts, holding a Carlsberg beer in one hand and a cigarette in the other. And it is precisely this photograph that Banksy used as his reference for Nighthawks.

From “The Urban Art Association,” 2007:

Description: Harvey Haddock, Banksy’s “Topdog”!

Location: Banksy Exhibition – Crude Oils, Westbourne Grove, London W2, 14/10/05

Occupation: Hazardous

From Mr. Eggs’ website:

"I guess you have worked it out that it was me who hit Banksy’s Crude Oils Show with a rather lame imitation of his work so it would fit in.

But I didn’t know they was going to be that fookin’ big, so it stood out like a sore finger anyway. Thanks to Harry the Haddock for answering his mobile phone so I could stick it on the wall.

They even kept it up for the whole show and gave it a name tag. Well, I had to hit London—and what better place and time to hit it up. Thanks to the Monorex Team for the night out and painting kinda session.

Cheers Banksy & Steve for an excellent show—see you soon."

Reply from the seller:

"Hi, Harvey has worked for Banksy on a number of things. He has done photos for him, and he also modelled for him on his painting Nighthawks. Banksy also dedicated one of the six Think Tanks from the site in East London to Harvey’s son, Orson."

Mr. Eggs is an artist who sneaked into Banksy’s exhibition and stuck one of his own small works onto the wall—Banksy style.

Haddock depicted in "Nighthawks".

Haddock at the "Crude Oils" exhibition pointing at him self.

Juliens Auctions - 2024 the Lazarides sale. Lot #48 - backside of a Banksy sketch.

Photo taken by Banksy as his study for "Nighthawks".

Haddock with a version of Think Tank aka Tank Lovers. From Creek Street, London. Several versions were made at various locations in London.

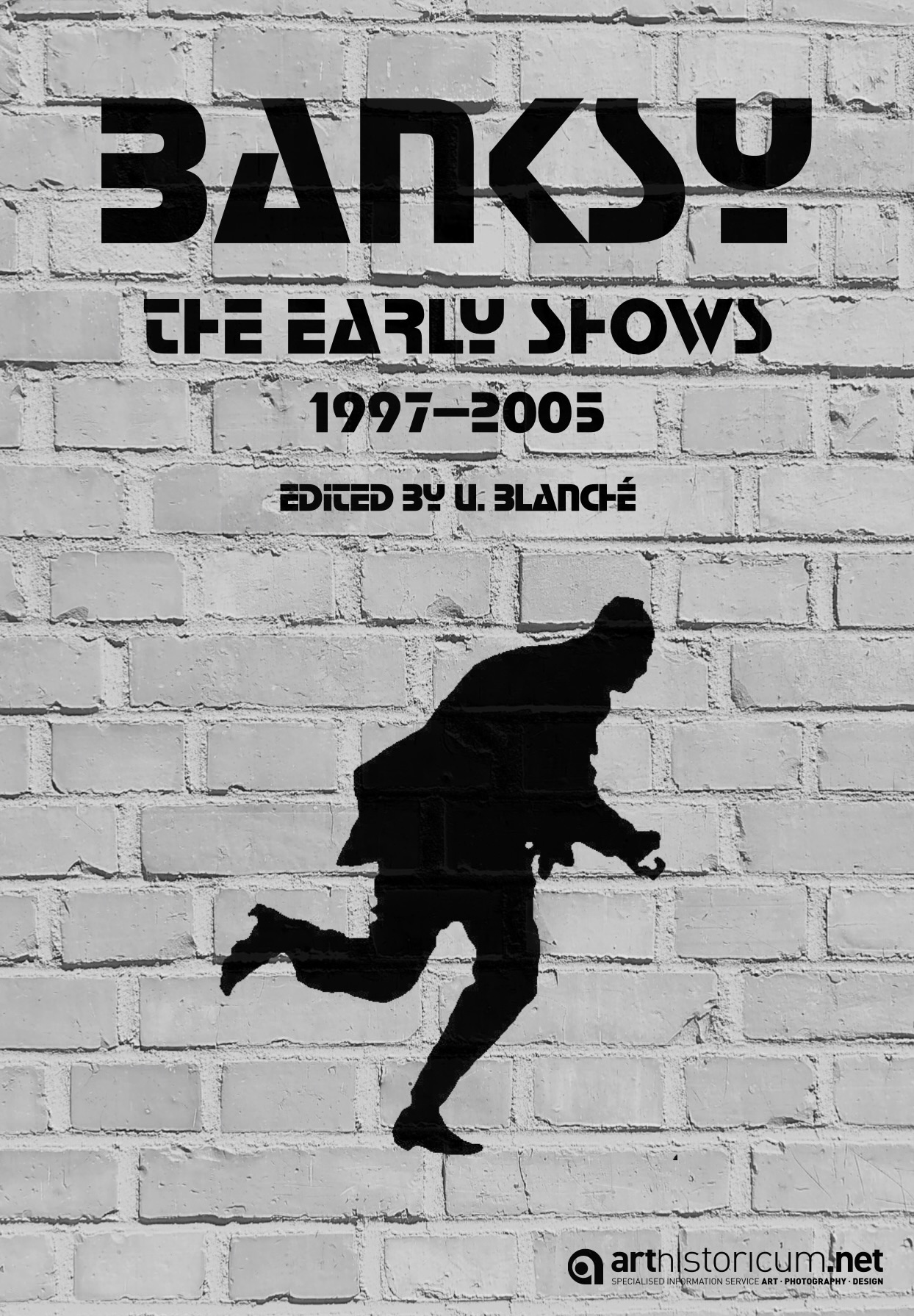

A very detailed overview of Banksy's early shows can be downloaded here. Banksy: The Early Shows 1997-2005, written and edited by Ulrich Blanché. Click on the image to download your free open-source copy. It opens in a different link. Published here with permission from the author. 324 pages.